Tissue injury or infection results in the development of a rapid local inflammatory response, a cascade of events necessary for the clearance of invading microbes, the minimization of tissue damage, and finally the restoration of normal tissue function, or resolution. The resolution phase occurs without compromising host defenses. Similarly to other biological cascades, the inflammatory response is shaped by the balance of positive and negative feedback loops, and requires the coordinated action of many different cell types. Among these cell types, phagocytic cells play a major role. However, these cells are not only involved in the initiation and development of the inflammatory response—through a process called efferocytosis, they also participate to resolution of inflammation, subsequent tissue repair and maintenance of tissue homeostasis.

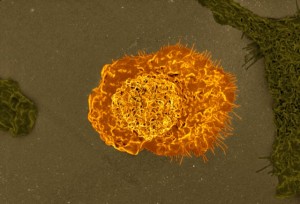

Efferocytosis, from the Latin efferre—translated as “carry out for burial” or “carry to the grave”—refers to the removal of corpses, or phagocytic clearance of dying cells and cellular debris. It is performed mostly by macrophages, which gobble up all sorts of bodies, and is orchestrated through the classical set of “find me,” “eat me,” and “tolerate me” signals. Failure in the process of efferocytosis may lead to unchecked inflammation, autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematous and rheumatoid arthritis, or other disorders.

Another cell type involved in the inflammatory response is the T regulatory cell. T regulatory cells, or Tregs for short, suppress the inflammatory activity of both innate and adaptive immunity, and secrete proteins involved in tissue repair. Results from a study published this month in the journal Immunity show that Tregs boost the ability of macrophages to carry out efferocytosis during the resolution phase of the inflammatory response.

For the study (Regulatory T Cells Promote Macrophage Efferocytosis during Inflammation Resolution), researchers used 3 in vivo models of inflammation— zymosan-induced peritonitis, lipopolysaccharide-induced lung injury, and advanced atherosclerosis. The found that, in zymosan-induced peritonitis and lipopolysaccharide-induced lung injury, Treg cells increase in the early resolution phase, and their depletion decreases efferocytosis. In addition, they found that in advanced atherosclerosis—a disease that involves defects in efferocytosis and resolution—efferocytosis is improved by the expansion of Treg cells.

The researchers also identified the specific sets of events leading to the enhancement of efferocytosis mediated by Treg cells. The first of these events is the secretion of interleukin-13 (IL-13) by Treg cells. In turn, IL-13 stimulates production of interleukin 10 (IL-10) in macrophages. Then, autocrine-paracrine signaling by IL-10 induces the guanine nucleotide exchange factor Vav1 in macrophages. Finally, Vav1 activates the GTPase Rac1, enabling macrophages to optimally internalize apoptopic cells.

The researchers suggest that therapeutic interventions able to boost the Treg cells/IL-10/IL-13 axis might help prevent disorders associated with impaired resolution, including atherothrombotic disease and the pathophysiological consequences of sepsis and inflammatory lung disease.

After learning the process by which T(reg) cells enhance macrophages ability to perform efferocytosis, I was curious about the ways that we could use this information to treat various inflammatory diseases. Given how much more common heart disease is and knowing that atherosclerosis is exacerbated by long term inflammation, I sought a paper that studied ways to prevent it by focusing on the use of T(reg) cells and any of the interleukins mentioned in this blog post. I found the attached article by Kimura et al, where they used different peptides of apolipoprotein B, one of the proteins that form LDL, and bound them to MHC II. They wanted to determine whether these vaccines could cause T(reg) cell activation within atherosclerotic mice and reduce the atherosclerosis. The vaccines were able to provide a way to treat atherosclerosis by activating the T(reg) cells and improve the condition of the mice. They did note that although their results showed that the effect of the vaccines were due to T(reg) cells, that other cells that produce IL-10 may also have an effect and more research will be needed.

http://ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28087520

It’s interesting that you looked at Tregs and vaccination, because I saw a similar research that studies the effect of Tregs on vaccine-induced immunity. Even though they are important in anti inflammatory responses and maintain homeostasis, they can suppress vaccine induced immunity and will result in poor clinical benefit. For example, when studied in HIV infection, Tregs were needed during acute infection, but weren’t beneficial during chronic infection, because they repressed anti-HIV responses.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5041024/

T-regulatory cells definitely play a role in upregulation of efferocytosis during the inflammation response. Macrophages are one of the more prominent immune cells associated with T-regulatory cells. T-regulatory cells secrete a variety of cytokines that stimulate the activities of macrophages. Based on studies involving injury, the number of T-regulatory cells was an indication of the effectiveness of efferocytosis. Progression of particular diseases like atherosclerosis tends to follow when there is a drop in T-regulatory cell levels.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30291029

Efferocytosis is a mechanism that allows the body to get rid of apoptic and infected cells, to avoid secondary necrosis and unnecessary inflammation that can lead to autoimmunity if the apoptic bodies release their intracellular contents. But in some cases, the efferocytosis can be avoided by the pathogen, such as bacterial pneumonia, when the Staphylococcus aureus is able to impair alveolar macrophages through the activity of factor alpha toxin, which manipulates their antimicrobial properties, and can no longer engulf the infected neutrophils.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5064327/

Like cytokines, T-regulatory cells have a role in the inflammatory response. These cells can upregulate the phagocytic activities of cells like macrophages, making them better at carrying out the destruction of foreign invaders. Without these T-regulatory cells upregulation, the host can fall victim to a variety of autoimmune disorders. T-regulatory cells can downregulate the activity of cells that are autoreactive and in doing so prevent the occurrence of autoimmune diseases. In diseases like rheumatoid arthritis, there have been studies that show a prevalence of T-regulatory cells which further support the idea that it does have immunosuppressive capabilities.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15457445

After reading this post about efferocytosis, I thought that this process was actually pretty cool and intriguing. It made me realize there is more to inflammation. I knew an immune response for a pathogen would include inflammation, but I didn’t think of how the host system would go back to its normal conditions after the attack. This is where the mechanism of efferocytosis comes in. It is a process that allows for cells to get rid of dead or infected cells at the site of infection. It inhibits unregulated inflammatory responses in the host, bringing the inflammatory process to a close. So now, I am thinking what other factors influences the efficiency and productivity of efferocytosis or bring about an end to inflammation? I figure that efferocytosis needs to be regulated very tightly.

One area of research focuses on an intracellular signaling pathway affecting efferocytosis. It focuses on the production and regulation of specialized proresolving mediators or SPMs. These are molecules that inhibit the proinflammatory signals, increases the rate of efferocytosis, and triggers damage to host without causing additional damage. Depending where this molecule is localized in macrophages, it can stimulate and activate a cytoplasmic enzyme called 5-LOX. By targeting the receptor tyrosine kinase called MerTK and its signaling pathway, the researchers were able to link different intracellular factors that help regulate efferocytosis: the activity of the CaMKII signaling cascade and calcium concentration, the movement and activation of 5-LOX to produce SPMs such as lipoxins.

The relationship between the activity of CaMKII and the MerTK pathway is highlighted throughout this research. The deregulation of CaMKII by MerTK seems to cause a positive feedback response in the MerTK signaling pathway, which causes an increase in efferocytotic function in macrophages and helps to conclude inflammation in the site of infection. At some point, the researchers show that by eliminating CaMKII in their experiments that the MerTK pathway is upregulated. Another key point in this research is the function and role of Gas6. Gas6 is a ligand from an infected cell or a cell going through apoptosis. These cells are targets of the macrophages. The Gas6 ligand will bind to the MerTK receptor on macrophages in order to activate efferocytosis and increasing inflammation resolution.

By activating this pathway, it seems like a good way to regulate inflammation and being a solution to inflammatory diseases. However, it is suggested this pathway might interfere with other signaling pathways the are needed, so before it can be a treatment to inflammatory diseases more research needs to be done.

https://www-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov/pubmed/30254055

Correction to my link https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30254055

The previous one didn’t work

A conventional treatment for autoimmune diseases is immunotherapy. Immunotherapy’s job is to take control of a person’s over-reactive immune system. This has been a novel approach for decades now, and even newer treatments involving expanding Treg cells ex vivo are beginning to emerge. A more difficult challenge is suppressing Treg cells. You would want to contain Treg cells in patients with cancer because they can influence tumor growth. It is not entirely understood the role of Treg cells in tumors. Precisely how do Treg cells get into tumor cells and what is keeping the Treg cells stable once they are inside tumor cells. I do think finding a way to suppress Treg expression is an excellent step in the right direction to find a treatment and possibly a cure for cancer.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30310234

Although I knew what the role of a macrophage was, this article expanded my knowledge and gave me a better appreciation for the job that it does. I never considered what an important role the macrophage has on the healing process of the body. The article mentions atherosclerosis and the fact that it is connected to malfunctions in the efferocytosis process. I found an article that expands on this idea and learned that during atherogenesis, the efferocytosis mechanism is impaired. This allows dangerous amounts a plaque to accumulate on artery walls because the so called “eat me” ligands that govern the edibility of cells undergoing programmed cell death is malfunctioning. The efferocytosis mechanism is a major determinant in how much plaque accumulates on an artery wall but also a major way to prevent plaque progression.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28137963

After reading about how regulatory T-cells help with the process of efferocytosis I wondered how inflammatory resolution occurs and how neutrophils are stopped. I found an article that demonstrated that clearance of neutrophils after LPS injection was more rapid when IL-10 was introduced to the surveying macrophages. Given that these Tregs induce release of IL-10 in macrophages in a paracrine fashion. In turn this helps with resolution and phagocytosis. Logically it seems that clearance of neutrophils is aided by Tregs. However, does the release of IL-10 and the subsequent removal of neutrophils cause an almost refractory period? Where even if an infection were to occur, would the neutrophils be able to respond?

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8897903

T-cells help with the process of efferocytosis I wondered how inflammatory resolution occurs and how neutrophils are stopped. I found an article that demonstrated that clearance of neutrophils after LPS injection was more rapid when IL-10 was introduced to the surveying macrophages. Given that these Tregs induce release of IL-10 in macrophages in a paracrine fashion. In turn this helps with resolution and phagocytosis. Logically it seems that clearance of neutrophils is aided by Tregs. However, does the release of IL-10 and the subsequent removal of neutrophils cause an almost refractory period? Where even if an infection were to occur, would the neutrophils be able to respond?

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8897903

As I am reading through the article, a question popped up in my mind. What is the rule of Tregs in type 1 diabetes? As we know type 1 diabetes is referred to chronic condition of lack or no production of insulin from the pancreas. The immunological definition for type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disease caused by autoreactive T lymphocytes attack against pancreatic islet β cell. So, what if further research conducted in the field of Tregs role and better understanding lead us to a cure! I found this article about altered expression of CD39 on memory regulatory T cells in type 1 diabetes patients. This study investigates the role of CD39 expression and both memory and resting T cells. They found out that patients with T1D have higher levels of memory T cells and lower CD39 expression. They referred the defective function of the Treg to the low expression of CD39 on memory Treg.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30318734

the previous link did not show up

Efferocytosis or the removal of dead cells and cellular debris by macrophages after an immune response is vital to the health of an organism. Without it, cytokines left in the interstitial space after an immune response cause other nearby immune cells to become activated and thus start a false inflammatory response.

For efferocytosis to occur, macrophages must recognize phosphatidylserine (PtdSer) on the cell surface of dead cells serving as an “eat me” signal. However, Kawano et. al. points out that certain defects prevent macrophages from recognizing the “eat me” signal expressed by dead cells. This causes the dead cells to remain in the interstitial space until further necrosis causes rupture of the cell membrane and thus release of cytokines that lead to a chronic inflammatory response. If the issue remains unresolved, one will acquire the autoimmune disorder, systemic lupus erythematosus.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30165442

Efferocytosis – the phagocytic clearing of dying cells and cellular debris. My immediate thought was: what would happen if efferocytosis were not regulated properly or went completely unregulated. I then chose to focus my thought in particular, on lung disease.

COPD or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is a that entails both chronic bronchitis and emphysema. There are over 3 million cases. per year. There is evidence that suggests that defective efferocytosis contributes to the presence of apoptotic cells in the lungs which contributes to COPD. Patients with COPD tend to have altered expression of the proteins that directly relate to efferocytosis.

Those findings indicate to me that efferocytosis should be more closely studied. I see value in pursuing this research in order to potentially create a viable immunotherapy drug that can correctly regulate efferocytosis and improve apoptotic clearance thus improving the quality of life in COPD and many other lung disease patients.

Reference article:

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3673667/

From reading the article, I was most intrigued about the effects by which Tregs has on our body. Especially Tregs ability to induce tissue repair in a plethora of tissue types that include “skeletal and heart muscle, skin, lung, bone, and the central nervous system.” Although it is quite important that Treg stimulates macrophages to engage in efferocytosis, I believe if more research is put into understanding just how these immune cells work cell regeneration, we can possibly unlock new means of utilizing regenerative medicine; hence, ameliorating and possibly curing type 1 diabetes that is a result of no insulin production due to degraded insulin producing beta cells in the pancreas’s islet of langerhans.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29662491