Our understanding of the risk factors for heart disease, the related prevention programs, diagnosis and treatment are continuously improving. At the same time, there are many unknowns that need to be studied. After all, heart disease kills more people than any other disease in the U.S. and worldwide. One of the questions in search of an answer centers around the mechanisms that lead to the repair of the injured heart. These mechanisms involve cells of the immune system, and especially cells dubbed mononuclear phagocytes, which include monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells. These cells modulate — either increase or suppress — the healing process of the injured heart.

Results from a new study (Embryonic and adult-derived resident cardiac macrophages are maintained through distinct mechanisms at steady state and during inflammation) published two days ago (January 16, 2014) in the journal Immunity, show that there there are two major types of macrophages involved in the healing process of the injured heart. One type appears to promote healing, whereas the other type drives inflammation, which is detrimental to long-term heart function.

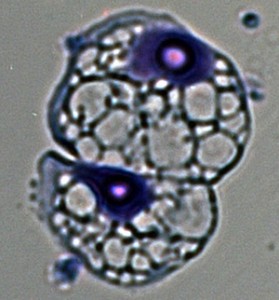

Photo credit: Slava Epelman, MD, PhD

“Macrophages have long been thought of as a single type of cell,” said first author Slava Epelman. “Our study shows there actually are many different types of macrophages that originate in different places in the body. Some are protective and can help blood vessels grow and regenerate tissue. Others are inflammatory and can contribute to damage.”

Macrophages are involved in the elimination of pathogenic microbes as well as damaged and dead cells and also participate in the activation of other cells of the immune system. They are present in nearly all tissues and, historically, have been viewed as deriving from white blood cells called monocytes, which originate in the bone marrow and circulate in the bloodstream. However, recent studies indicate that most populations of tissue macrophages are established embryonically, persist into adulthood and, in the absence of inflammation, maintain themselves at specific locations by proliferating.

“Now we know it’s more complicated,” Epelman said. “We found that the heart is one of the few organs with a pool of macrophages formed in the embryo and maintained into adulthood. The heart, brain and liver are the only organs that contain large numbers of macrophages that originated in the yolk sac, in very early stages of development, and we think these macrophages tend to be protective.”

The researchers carried out their studies in mice and showed that healthy hearts maintain the population of embryonic macrophages along with a smaller population of adult macrophages derived from blood monocytes. However, during cardiac stress — as for example stress generated by high blood pressure — the embryonic macrophages are replaced by adult macrophages derived from blood monocytes.

Developmental considerations may help explain the role played by the two different types of cells. Embryonic macrophages may encourage healing by carrying out functions that, in general, help a developing embryo — for example, encourage growth as well as proper tissue organization and structure, while at the same time eliminating damaged or dead cells. On the other hand, adult macrophages originating in the bone marrow and circulating in the blood participate mostly in the inflammatory process in order to control infection.

“Now that we can tell the difference between these two types of macrophages, we can try targeting one but not the other,” Epelman said. “We want to try blocking the adult macrophages from the blood, which appear to be more inflammatory. And we want to encourage the embryonic macrophages that are already in the heart to proliferate in response to stress because they do things that are beneficial, helping the heart regenerate.”

Copyright © 2014 Immunity Tales.

Working in the field of medicine and having a large part of my responsibility designated in heart and vascular disease, this article presents an interesting approach to recovery following a rather risky procedure. The heart as we know is essential to our vitality and with the increasing number of heart complications and eventual interventional procedures performed each year, healing our hearts has surfaced as a popular topic across the medical spectrum. With new developments in macrophage differentiation, there are many questions that come to mind about how this treatment will prove to be not only effective but how it can become more readily available. First, at what period or rate of decline do the “healing” macrophages begin decreasing in our system? If our bodies naturally provide a particular set of conditions at birth where these macrophages seem to be more abundant, what changes are naturally occurring in our system that cause these numbers to diminish in adulthood? Second, if continuous research is being done on stem cells and their ability to evolve into a multitude of cells, could these be harvested (cord blood, etc.) and be put into environments that would result in growth of the healing-type macrophages? Another question, how can researchers and healthcare professionals prevent inflammatory macrophages from interacting with injury site, as edema in areas in or around the heart could prove to be fatal? Lastly, following cardiology procedures if patients were given a dose these macrophages what are the potential risks as well as the benefits that an option like this could provide to a patient during the healing process? I would love to see this research become a staple solution in the future as it could truly increase the number of successful outcomes to those who have a “broken heart.”

Like all aspects of life, there seem to be pros and cons. The macrophages of the body seem to be no different. Macrophages are amazingly dynamic in their ability to modify themselves from early stages as a monocyte into a number of different forms in order to fight infection. What better first line of defense? This article is interesting in that it addresses embryonic macrophages and their prominent role in beneficial cardiac function. However, the name itself is concerning… By embryonic does that mean we are born with a limited number? Do these beneficial cells decrease in number as we age?

I think what is meant by embryonic macrophages is that these macrophages “originated in the yolk sac” hence the term embryonic. It would seem that these embryonic macrophages are limited in number only by their capacity to proliferate within the tissue. I imagine that it is this limitation that causes the adult macrophages, originating from the bone marrow, to show up to support the embryonic macrophages. The real question is why do the adult macrophages induce inflammation, while the embryonic macrophages repair? And if the inflammation caused by the adult macrophages is damaging why does occur? Does it have a better outcome than not having an inflammatory response?

As a student in anatomy and physiology studying the cardiovascular unit as we speak, this article is extremely interesting and poses lots of questions. The embryonic macrophages work to repair and heal the heart without the threat of inflammation and further damage. However, my only concern is the mechanism of approach for both the embryonic macrophage and the adult macrophage. Has enough research been executed to prove that the embryonic macrophage can adequately fullfill the proper immune response to eradicate pathogenic threat? We all know the negative effects that the adult macrophage can pose in cardiac tissue including inflammation and edema in the involved tissues; however scientists are knowledgeable that this mechanism is effective in eradication though cascading events that enlist the help of other immune system players.

I can understand that there would be two different types of macrophages for different stages in life. It makes sense that there would be specialized macrophages for an embryo to prevent the developing organism from irreversible harm to such critical bodily organs. However I do question how effective these embryonic macrophages are in the fight against certain pathogens that would typically not be encountered as an embryo, but as an adult. So yet another question comes to mind…do we have the adult macrophages to compensate for major pathogens that the embryonic macrophages cannot tackle? Clearly there is a purpose for both sets of macrophages. However, as the adult macrophages seem to pose a threat in their quest to improve bodily tissues, it seems somewhat unfair to bypass or ignore them and their purpose. Nontheless, this new study is very interesting, and I am excited to hear and see new innovations and their effectiveness.

I agree with you on the significance of the adult macrophages even after injury to an organ, and I agree that blocking them would do more harm than good. However, in the treatment that is being described in the article, we’re not talking about complete blockage of these adult macrophages. If we were to completely block them from entering the site of injury, we’d be opening up a window for pathogens to take hold of the site without any interference on our part. What I believe would be more proper to do, and what I believe is being described in the article, is to decrease the movement of adult macrophages into the area surrounding the injured heart, for example, enough to allow for embryonic macrophages to do what they do best, heal. This would moderately control pathogenic infection, and would keep inflammation from occurring, thus, preventing damage to the surrounding tissue that we want to recover.

The article points out that these embryonic macrophages are found in substantial amounts in not only the heart, but also the brain and liver. This gives me reason to believe that in the future we could be using this knowledge not only to treat people suffering from cardiac problems, but possible liver and brain damage, if not more. One of the previous comments brought up the idea of stem cells and whether or not we could use them to help raise the number of embryonic macrophages, and that brought up a question in my mind. Could we use these embryonic macrophages in place of stem cells to stimulate healing and recovery in other organs? And, are embryonic macrophages able to move around in the body, or do they stay localized in those large pools in the heart, brain, and liver? Because if they are not required to stay where they proliferate, we could use them to heal other parts of the body as well.

As we learned in class, blood cells and some tissue cells all form from hematopoietic stem cells (1). Both embryonic and adult macrophages develop from stem cells. The important difference, as stated above, is that embryonic macrophages are only created embryonically, then persist into adulthood. Adult stem cells, on the other hand, continually proliferate and develop from the hemtopoietic stem cells found in bone marrow throughout life.

Using embryonic stem cells to develop these embryonic macrophages brings up a controversial and ethical issue. However, it may be a solution to those that have lost many of their beneficial embryonic macrophages. Whether or not it is possible to transfer these cells to another host seems like a bigger problem to solve. It is very likely that they would not be compatible for a new host. One reason I could think of is that the host immune system would recognize these cells and defend against them instead.

Reference:

1) The Immune System, Peter Parkham, Third Edition (Chapter 1, pg 14).

Generally macrophages are localized in the tissue in which they are present. However, it would be very interesting if in fact the embryonic macrophages have the ability to circulate or not. Very interesting point considering the embryonic macrophages are so different from general macrophages.

It is known that macrophages are the primary cells involved in causing plaque buildup in arteries, known as atherosclerosis (1). Atherosclerosis is one of the most common causes of cardiovascular disease, so learning to regulate macrophage activity is a worthy area of focus. Other posters above believe that scientific research should be more focused towards using stem cells to create more embryonic macrophages. However, this is a much more complicated task, as it involves implanting immune system cells into another host.

I agree with Epelman, who states that we should try to instead target adult macrophages, which are more inflammatory. However, this is still not an easy task. Macrophages are essential in the immune system, so inhibiting them too much could cause more serious problems by compromising immunity. Further studies need to be done to differentiate the embryonic and adult macrophages more precisely. Understanding their mechanisms of proliferation better could help create pharmaceuticals that target and inhibit only a certain amount of adult macrophages that directly affect the heart and cause atherosclerosis.

References:

1) Lucas AD, Greaves DR (November 2001). “Atherosclerosis: role of chemokines and macrophages”. Expert Rev Mol Med 3 (25): 1–18. doi:10.1017/S1462399401003696

The article was interesting to me since I learned new information about the macrophages. The article informed me that there is different types of macrophages. Macrophages are phagocytic cells of both the innate and the adaptive immunity. Everyone thought there was only one type of macrophage. As technology and science is improving, scientists are learning new things about the body. The human body is a complex system and there is still things that people do not know about human body.

It is interesting that the heart has both macrophages from the embryo and some amounts from blood monocytes. The heart is a very important organ for human beings to live; people need to learn more about the heart and understand it. As one of my few students mentioned in the blog (ics100190), learning new information about the heart will result better treatment and medication since heart disease are the leading causes of death not only in the United States but also worldwide.

Before the new information about macrophages, people thought that macrophages ascended from blood monocytes that circulated in the blood. It also becoming very clear to researchers and scientists that resident macrophages expand at the original site of proliferation instead of the recruitment of blood monocytes (1).

Sources:

Epelman, S., Lavine, K. J., Beaudin, A. E., Sojka, D. K., Carrero, J. A., Calderon, B., & … Mann, D. L. (2014). Embryonic and Adult-Derived Resident Cardiac Macrophages Are Maintained through Distinct Mechanisms at Steady State and during Inflammation. Immunity, 40(1), 91-104. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2013.11.019

With heart disease killing more people than any other disease, you would think there would not be so many unknowns. This article is very interesting and brought up some terminology that I have never heard of like embryonic macrophages. It makes perfect sense that we would have a set of macrophages that would be specific to us as an embryo, but then again I don’t understand why there is only a small amount of these set aside to help us in the future. If we have a cell that is so valuable to us and could help us heal at a more advanced rate with few disadvantages you would think our body would have produced a lot more or be able to produce as much as needed.

Another thing, why hasn’t our body came up with a mechanism to control how much of which macrophage to send to the site that needs healing or inflammation. It seems that over the decades our bodies would have this nailed by now, does this mean that we have no way of controlling this our selves, or will this process have to be “man made”. Like others said before there is no reason to block the adult macrophages from entering a site that they will or eventually will be needed but to monitor the amount of the macrophages that are realaeased into the area.

My questions about the article that confuse are what do they mean about the macrophages being protective? protective of what, are we saying they are protective of the organs that they are found in or are they protective of themselves? Another concept I didn’t understand is when they say the macrophages are converted to adult macrophages, are they saying the embryonic macrophages are replaced or that they proliferate into adult macrophages. I guess either way we loose the embryonic macrophage?