Memory can be defined as the capacity of a system (usually the brain) to store and recall information on previously encountered events. Immunological memory—which can be induced by either natural infection or by a vaccine—refers to the ability of the immune system to respond more rapidly and effectively to an infectious microbe that has been previously encountered. It is considered one of the most significant features of the adaptive immune system. However, immunologists do not fully understand the mechanisms at the basis of memory responses. Indeed, the definition of immunological memory itself continues to evolve, being shaped by new discoveries and developing hypotheses. As of now, immunologists are still debating whether or not the innate immune system is capable of developing memory responses.

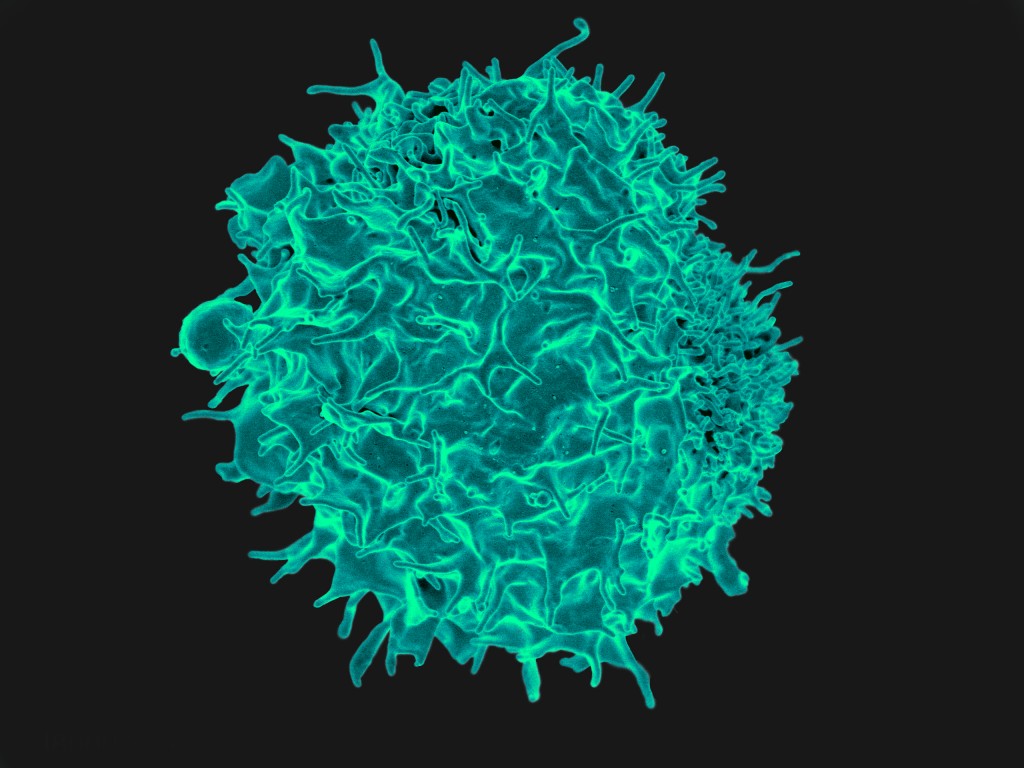

Donna L. Farber (Columbia University Medical Center), recently provided her own definition of immunological memory: “I would define immunological memory on the basis of three main criteria. First, memory immune cells should be long-lived and maintained independently of stimulation or persistence of antigen, either through homeostatic turnover or long-term stable maintenance. Second, memory immune cells should be specific for a particular antigen or epitope. Third, a memory immune cell should be intrinsically changed by the previous encounter with antigen; for example, be functionally enhanced and respond more quickly and effectively to repeat encounters with a specific pathogen and/or antigen. Memory T cells and B cells certainly fulfil these criteria, but it could be extended to other types of immune cells, such as natural killer (NK) cells.”

But, what are the molecular mechanisms required for the establishment and maintenance of immunological memory? Results from a new study, which focuses on T cells, indicate that extensive chromatin remodeling reprograms immune response genes toward a stably maintained “primed” state characterized by imprints in the chromosomes contained within these immune cells. A single cycle of activation is sufficient to leave behind the imprints, which correspond to genes that need to be switched back on as soon as immune cells are reactivated following re-exposure to the specific antigen. The imprinting occurs prior to terminal differentiation of the T cells, forming the basis for the long-term memory that allows an immediate response once the cells are activated for a second time.

Peter Cockerill, senior author of the study, explained in a press release: “The initial immune response switches on certain regions within chromosomes of previously inactive T cells to leave them in a more open structure so that they can then sit poised, ready to respond much faster when activated again in the future.”

The “priming” mechanism is able to silence the immune system until it needs to be activated again in order to fight infection, thus avoiding the risk of damaging cells that are part of the host. While the T cells remain poised, they do not produce molecules involved in the inflammatory response that is used to fight infection, thus preventing inflammatory or autoimmune disorders that may target healthy host cells instead of foreign invaders.

The immune system is divided into the innate immune system and the adaptive immune system. As the name indicates, the adaptive immune system is able to respond faster and more efficient to secondary infections than to primary infections. This ability is enabled by immunological memory in lymphocytes. But how can a cell respond quicker to a secondary infection than to a primary infection? Research performed by Peter Cockerill shows that there is a chromosomal change in T cells during a primary infection that allows T cells to respond more aggressively to secondary infections. This is referred to as “priming”. Understanding this priming mechanism even further could be vital for synthesizing new vaccines that could trigger more production of primed state immune cells than the current vaccines produce. This will give patients a better ability to fight off infections once they encounter the real pathogen they were vaccinated for. However, can this priming mechanism be applied to the innate immune system as well? Can we have an innate immune system that also has immunological memory? According to Donna L. Farber, the only cell of the innate immune system that could potentially have immunological memory is the NK cell. The other cells of the innate immune system are neither long lived nor specific to an antigen which are two categories that Donna L. Farber considers as a requirement for having immunological memory. Furthermore, in research performed by O’ Leary et al, NK cells were shown to have memory-like capabilities as they elicited contact hypersensitivity reactions to a specific hapten up to four weeks in the absence of B cells and T cells in mice. When T cells, B cells, and NK cells were absent, contact hypersensitivity was absent. This is important because the only cells that were known to be capable of eliciting contact hypersensitivity were T cells and B cells which are known to have immunological memory. In all, understanding immunological memory more in depth can lead to more efficient vaccines that trigger memory from both the innate and adaptive immune system.

Yes, T cells and B cells do have the ability to express memory. Furthermore, you have provided evidence that Natural Killer cells have the ability to express memory as well. But if T cells and B cells use priming in order to express memory, then I wonder what memory mechanism Natural Killer cells use. I also wonder if this mechanism is dependent upon T and B cells. Natural killer cells are cytotoxic lymphocytes that attack infected cells during the innate immune response. Now that it has been proven that they are able to exhibit adaptive immune characteristics, research has presented one of the mechanisms that it might use. First off, natural killer cells are similar to T cells because they both express a specific killer-cell receptor. Progenitor T cells expressing this receptor are able to create an abundant of memory T cells and interestingly are able to make memory natural killer cells! The production of the memory natural killer cells is completely dependent upon the amount and success of this particular progenitor T cell. So to add to your response, Juan, Natural Killer cells are definitely capable of memory and this is just one mechanism on which it can happen.

http://www.cell.com/cell-reports/fulltext/S2211-1247(14)01054-7

In your comment you mention the fact that according to Donna L. Farber the only potential cell of the innate immune system that could have the ability to have immunological memory is the NK cell. There is a recent study that might support Donna L. Farber idea. Research conducted in a study showed that NK cells have some form of immunological memory in rhesus macaques. In the experiment involving these primates, the rhesus macaques were vaccinated twice with a six month duration in between each vaccination. The vaccination involved the use of adenovirus serotype 26 (Ad26) that expressed HIV-1 Env (the serotype of this virus was incapable in replicating) or a second vaccine of adenovirus serotype 26 that expressed SIVmac239 Gag. After being vaccinated, rhesus macaques were not exposed to the virus for a period of five years. Once the five year period was over, researchers tested the NK cells of the rhesus monkey vaccinated for its ability to lyse dendritic cells with the same viral antigen used in the vaccination. The researchers found out that splenic NK cells and hepatic NK cells were able to lyse dendritic cells with the same antigen used in the vaccination in a efficient manner. It should also be noted that the NK cells had little response to dendritic cells that had the antigen from the different vaccine. Nevertheless if NK cell have the potential to have immunological memory this could possibly mean that the effectiveness of the innate immune system to take care of pathogens can be enhanced. Information gathered from this study can also be used to develop vaccines to fight against HIV-1.

I like the idea that vaccines could be created based on the memory cells of the innate and adaptive immunity. I am currently taking virology at GSU, and we learned that HIV infiltrates the host genome, thus going through the lytic and lysogenic cycle. Which ultimately means it integrates in to the host genome and can cause acute infection then also in the lytic cycle it can lyse the cell and spread to other host cells. Priming is very important in developing a memory response in innate and adaptive immunity when it comes to pathogens that can enter the host genome and can be lysogenic, activating and inactivating throughout the hosts’ life time. It would be beneficial if scientist can come up with a way to prime all the healthy cells in a human host with an inactivated HIV sub-unit vaccine. This would provide preventative measures to sexually active people and potentially eradicate most of the virulence associated to this virus. An obstacle to get around is the mutation rate of HIV, do you think this idea is clinically possible for a virus such as HIV-1?

I totally agree with you and to answer your question that can we have an innate immune system that also has immunological memory? I would say totally yes. In fact, according to the article that i found, innate immunity in many simple organisms, especially those who lack adaptive immunity, have the ability to be primed by previous infections, and they have stronger secondary responses when faced with the same pathogen. As an example, Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes, which are the major vector for the spread of Malaria in Africa, when previously exposed to Plasmodium falciparum showed enhanced immunity upon being reinfected by parasite.

NK cells are part of the innate immunity but evidence showed that they are closely related to T and B cells of adaptive immunity in many ways. For example, NK cells and T and B cells come from the same lymphoid progenitor. Moreover, immature NK cells are “educated” just like T and B cells, in the process to make functional effectors cells only from cells that are tolerant to self. Furthermore, both NK cells and T and B cells required the same cytokine to be able to develop and survive properly. To sum up, the reasons why innate immunity memory exist is because of the similarity of NK and T and B cells, and also because previous infections in simple organism prime them.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4410097/

Anytime the adoptive immune system is in use the exposure to the infection causes a quicker immune response than the previous, regardless of whether priming is used. I think what the article wanted to highlight about priming is the cell’s ability to specifically choose when activate / inactivate the immune response. It’s fascinating how having the ability to use memory cells to fight an infection could lead to such a phenomena such as the avoidance of unnecessary destruction of host cells. Hopefully scientists will be able to figure out away to get other cells of the innate immune system to produce memory cells like NK cells, so that they too can use priming as a mechanism.

http://immunitytales.com/a-priming-mechanism-contributes-to-immunological-memory-in-t-cells/

There is no denying the fact that the cells of the adaptive immunity are crucial in helping the host fend off against any pathogens or virus that the host may encounter during its lifetime. The ability of the cells of the adaptive immune system such as T cells to have immunological memory to combat infectious microbes in a quick and effective manner is beneficial to the health and survival of the host. The mechanism that the study provides on how might T cell are able to remember pathogens could be just one of many possible mechanism that can lead to one of the defining features of the adaptive immune system: immunological memory. There is another study on a possible alternative way of how the immune system is able to remember. As stated in the blog, T-cells are capable of memory. There is a protein known as Lck that plays a crucial role in helping T cells to remember. T cell that have never encounter a certain pathogen are known as naïve T cells. The protein Lck can help these naïve T cells by capturing the receptor template of the pathogen. In addition Lck can lead to increase amounts of T cells that confront the invading pathogen.

The blog also states that immunologist are still debating as to whether or not innate immunity is capable of developing memory response. Research has shown that there are possible adaptive traits of the innate immunity in plants. It is know that plants do not have an adaptive immunity. One process known as Systematic acquired resistance (SAR) can help prevent reinfection in plants. The mechanism mediating SAR are known to involve epigenetic processes that can contribute to innate immune memory. In addition plants also have cell surface receptors that can identify characteristic in pathogens. When these receptors are activated it can lead to the production of a signal known as methyl jasmonate which then can lead to defense response from the plant.

Your reference to SAR is very interesting. Hepatitis D virus (a satellite virus reliant on Hepatitis B virus for replication) has been thought to have evolutionary roots from an ancient plant viroid. This negative sense RNA virus does not require an RNA- dependent RNA polymerase (as many RNA viruses do) because the genome of Hepatitis D acts as a protein and demonstrates ribozyme function; thus epigenetic processes possibly led to the evolution of Hep D satellite virus infecting humans?

I bring this up because viruses (and bacteria) co-evolve with humans, animals, AND plants. If plants do not have an adaptive immune response to viruses, but were able to evolve to produce cell surface receptors that can identify characteristic pathogens from previous infections, then maybe NK cells really ARE capable of developing immunological memory. If Hep D is thought to be an ancient plant viroid that somehow evolved into a virus capable of initiating replication replication in humans ( in the presence of Hep B) virus, then wouldn’t it be possible for human NK cells to develop immunological memory in response to pathogens as well? Obviously an endless number of factors must be considered, but the take home message is that viral and bacterial pathogens evolve with us, so we are not outside the realm of possibility for human NK cells to respond to virus in the way plants have to viral infection.

Patrick, I really thought that plants not having an adaptive immunity was super interesting. If this were true they could save a lot of energy and use it in others areas, like maybe photosynthesis or growth. However, I found research that states otherwise. This research proves that all living organisms have an innate and adaptive immune response. Furthermore, in order for species to survive they must have an adaptive immune response. To relate to this article, no, plants do not use natural killer cells. However, if you refer to Figure 2 of my attached research article below, it shows that plants use PRRs and R-genes for innate immunity and RNAi for adaptive immunity. PRRs are pattern recognition receptors, R-genes are resistance genes, and RNAi is RNA interference. Another cool thing that I noticed is that even though they have an adaptive immunity, their memory seems to be expressed in the innate response. Pattern recognition receptors are used, and with this memory must be used in order for the plant to remember the pathogen. This would make them kind of related to memory natural killer cells, in the sense that they both express memory during an innate immune response.

http://www.weizmann.ac.il/immunology/NirFriedman/sites/immunology.NirFriedman/files/uploads/rimer_cohen_friedman_-_2014_-_do_all_creatures_possess_an_acquired_immune_system_of_some_sort.pdf

After reading your article about plants possessing both an adaptive and innate immunity I started to agree more with your position than Patrick’s. However, after doing my own research I too have found an article stating that plants lack an adaptive immune response. It seems that they possess an innate immune response but lack a built in adaptive immune response which could be comparable to our immunity. However, they are able to acquire an immune response, as mentioned above through SAR. Perhaps this is just a miscommunication in the classifications of the divisions of the immune system. SAR could be the comparable version of an “adaptive” immunity for plants.

Although there is that discrepancy, both articles do mention the memory aspect of immunity lies within the innate response as opposed to the adaptive response which is the case for humans. There is some debate now regarding which of the divisions possesses memory in humans, due to the classification of natural killer (NK) cells which seem to blur the lines between innate and adaptive. NK cells do much more that I thought they would do. It seems that most classes focus on the importance of lymphocytes and the innate-specific cells which are the first line of defense against the pathogen. It seems that NK cells have a hand in every single aspect of both innate and adaptive responses. They produce inhibitory and excitatory cytokines which affect antigen presenting cells (APC) a player in innate immunity required to help stimulate and activate an adaptive response. As well, they possess MHC I receptors along with many other on their cell surface which interact directly with CD8+ cytotxic T cells which are the major killers in the adaptive immunity. As well there is even evidence that the NK cells can adapt and even have an ability to remember. When mature NK cells were placed into a naïve host, they were able to pull from past events to become reactivated for a specific antigen when that antigen was presented.

So as we learn more about the two immune divisions it seems that they are more intertwined than previously believed. This opens the door for exploration into manipulating innate and adaptive cells in order to target specific cells or pathogens through mechanisms utilized through other immune cells. For example, if an innate cell such as a resident macrophage was able to have some memory capability, perhaps the protection against microbial infection would be even greater. The macrophage would take on a more robust role and may not even need to signal neutrophils to aid their attack. The possibilities are endless!!!

http://www.cell.com/cell-host-microbe/abstract/S1931-3128%2811%2900128-4?_returnURL=http%3A%2F%2Flinkinghub.elsevier.com%2Fretrieve%2Fpii%2FS1931312811001284%3Fshowall%3Dtrue&cc=y=

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3089969/

The fact that scientists are still debating about the functions and classifications of immune cells is no surprise. The immune system is complex as it is composed of cells, receptors, cytokines, proteins, and other molecules that interact with one another so that an individual can fight off infections and cancerous cells. In my opinion, NK cells should be classified under lymphocytes due to the resemblance that NK cells have to T- cells. Besides the similar characteristics between NK cells and T- cells that you mentioned, NK cells are also cytotoxic just like cytotoxic- T cells. In fact, they use similar mechanisms to attack virally infected cells or cancerous cells. They come into close contact with the target cell, induce a pore, and inject molecules that induce the death of the target cell. And now, research has shown evidence that NK cells can display immunological memory in the primate Rhesus macaques as Patrick mentioned above. This finding is important because primates have many resemblances to humans. The big question would now be, do human NK cells also display immunological memory? A problem with assessing this question is that doing research on humans is a more sensitive subject than doing research with mice. However, I would save samples of pathogens that caused infections in individuals that survived the infection without medical intervention (e.g. antibiotics), and then use a sample of their peripheral NK cells a month post infection to see if the NK cells respond more aggressively to the pathogen that was isolated from the infection a month back. If so, I would incline more with the classification of NK cells as cells of the adaptive immune system.

http://www.hemoncstem.net/article/S1658-3876%2814%2900108-3/fulltext

It’s very interesting to know that plants are able to exhibit adaptive immune-like responses without actually possessing an adaptive immune system. However, I think that comparing the plant immune system with the animal immune system seems rather arbitrary. There could be an evolutionary reason as to why we have developed an adaptive immune system. For starters we have more internal and external targets for many more pathogens to invade than most plants. It’s also possible that we receive more constant daily exposure to pathogens due to the tendency for human nature to interact with others. This could also be the reason as to why we have developed a system by which a myriad of infections can be alleviated.

In the context of evolution and this blog post, it also seems likely that the ability of NK cells to show memory-like characteristics could be a throwback to a time before we had an adaptive immune system. If there was a time when all we had was the innate immune system, then the NK cell’s memory-like characteristics could represent a time during evolutionary development when we were beginning to combat repeated invasions of pathogens that we constantly encountered. Once the adaptive immune system developed then the need for the NK cells to possess memory capabilities became less urgent over time. That’s not to say that we shouldn’t utilize this discovery to reinforce our immune system as it is far from perfect.

As mentioned in the by the blog, the innate and adaptive immune work together to combat infections and maintain the hosts’ health. The innate immunity is involved in first response to pathogens and usually goes into action immediately or within hours. It is composed of multiple cells like phagocytic cells, NK cells, dendritic cells; which initiate the adaptive immune cells thus is paramount in the whole immune response. Going by the definition of Donna L Farber, the adaptive immune system does not meet any of the criteria for having immunological memory (as of right now) i.e. most aren’t long-lived, specific and they don’t have an enhanced response at second exposure. The adaptive immunity usually goes into action within 24 hours and unlike the innate has immunological memory.

The results from the study on genes that encode for the “priming” mechanism of T cells during the adaptive immune response have great potential to be used for Adaptive T-cell immunotherapy. This therapy is usually used cancer cells and involves transferring tumor-specific T-cells from someone else to a cancer patient in an attempt to kill specific cancer cells. These immune response genes could be manipulated to create imprints in T-cells for specific cancer cells which usually display some abnormality like lower levels of MHC-1. These cancer-cell imprinted T-cells can then be put into a cancer patient and target those cells and perhaps be a potential cure.

Reference: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4327320/

Immunotherapy is a wonderful alternative and possible replacement for traditional cancer treatments like chemotherapy and radiation. In addition to the adoptive T-cell immunotherapy, monoclonal antibody immunotherapy is also being used for cancer treatment. Monoclonal antibodies are antibodies derived from b cells that came from a single b cell. The antibodies are tweaked to target malignant tumor cells expressing specific receptors and signaling. These tumor-targeting antibodies are able to block signaling pathways of abnormal cells, specifically growth receptors that enable the tumor to grow. They accomplish this by binding to those receptors and neutralizing the signal. In comparison to traditional cancer treatments, this is less harmful and could potentially have longer lasting effects. The ultimate goal is to stimulate a patient’s immune system to make these same antibodies and be cancer-free.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4350348/

http://www.bio.davidson.edu/molecular/MolStudents/01rakarnik/mab.html

I like how you considered coming up with a solution to curing a disease. The potential of using the priming capability of T cells as an immunotherapy is an interesting concept. The priming mechanism that T cells have is also being used to potentially prevent disease from occurring at all. Vaccination has led to a major decrease in incidence of several diseases. Unfortunately, there is not currently an effective vaccine against Mycobacterium tuberculosis in adults. There is currently a study being conducted that is close to entering human trials that uses strategic priming with multiple antigens to create efficient memory by vaccination to prevent TB. It focuses on having the appropriate ratio of memory cells which include central memory cells which are long lived and circulate in the lymph nodes, and effector memory cells which circulate through the blood and peripheral tissues. In order for the vaccine to be effective, T cell priming must be occurring in an antigen specific manner that produces most common antigens to cause an immune response. The priming mechanism must create an abundant amount of T memory cells, and the accurate types of memory cells, so that a safe and effective vaccine can be created against TB infections. The priming mechanism of T cells has the potential to defeat many other pathogens plaguing humans.

http://eds.a.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.gsu.edu/eds/pdfviewer/pdfviewer?vid=4&sid=e887c4a2-1204-4ec4-aa49-b378f36995fe@sessionmgr4003&hid=4103&preview=false

The article discusses immunological memory, what is it? Immunological memory is defined as a specific, prolonged response system that is maintained independent of stimulation and enhanced after each encounter. However, the article primarily focuses on how priming mechanism affects immunological memory in T cells. The study shows that when a chromosomal change occurs in T cells during first exposure to infection the second time exposure occurs the T cells will respond more rapidly and aggressively. This technique can be very beneficial to patients fighting off infection with vaccination because using priming mechanism allows for the immune system to only be active when needed to fight off the infection and turned off after so that damage will not be caused to host cells. The priming mechanism can be used in the adaptive immune system, but debates the ability of the innate immune system to be able to use the mechanism since it lacks memory response. Natural killer cells are the only cells in the innate immune system that can possibly use the priming mechanism. The natural killer cells work in both innate and adaptive immune system. They are the only mechanism in the innate immune system that use memory cells; mature NK cells are able to use memory cells to reactivate a specific antigen when needed. Questions that arise are whether scientists will be able to mutate genes of other innate immune mechanisms to be able to use memory cells like natural killer cells do. If the use of priming mechanism could be more widespread in the cells of the immune system, it could really benefit host cells and reduce the worries of them being destroyed by its immune system or vaccinations.

References

http://immunitytales.com/a-priming-mechanism-contributes-to-immunological-memory-in-t-cells/

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3089969/

Immunological memory has been the foundation of adaptive immunity and now in recent research finds that certain cells of innate immunity can also exhibit memory although not as specific as that of the adaptive immune cells. In an article I found, it stated that not only NK cells exhibit memory but also monocytes/macrophages and dendritic cells. These cells exhibit “trained memory” which basically can be due to either re-infection to same, similar or even different pathogen. And this non-specific memory heightens the innate immune responses to combat secondary infections. For instance BCG vaccine has been found to confer non-specific protection against un-related pathogens. Although the mechanism of action is still currently unknown, it’s been thought to be through non-specific activation and training of the innate immune system. This illustrates that not only the adaptive immune response is involved in memory due to vaccination but also innate. Overall the take home message is that apart from NK cells, other cells of innate immunity can also possess immunological memory. And just like Donna L. Farber says, the criteria for immunological memory could be extended to NK cells but also it should not be limited to that only.

C.M. Gardiner, K.H.G. Mills, The cells that mediate innate immune memory and their functional significance in inflammatory and infectious diseases, Semin Immunol (2016), http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.smim.2016.03.001