The 2014 Ebola epidemic began as a mysterious disease in a small village in Guinea at the end of 2013, but was not identified as Ebola until March 2014. From the original location near a tropical rainforest, it spread to major rural and urban areas across West Africa. Formerly known as Ebola hemorrhagic fever, Ebola virus disease (EVD), is a severe, often fatal illness in humans caused by the Ebola virus — the virus is transmitted to people from wild animals and spreads to the human population through human-to-human transmission. As of March 20, 2015, in countries with widespread transmission (Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone), there were 24,754 reported cases, with 10,236 total deaths.

Despite the high number of cases, the human immune response to Ebola virus has not been well studied, delaying the development of effective vaccines. The very limited availability of infrastructures, especially those equipped with the high containment level necessary for these studies, hinders progress in understanding the human immune response to the virus.

However, a few days ago, a study published in the scientific journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences described the immune responses of four EVD survivors who received care at a U.S. hospital. Rafi Ahmed, senior study author, said in a press release by Emory news center: “Until now, detailed studies like this in acute Ebola virus disease were logistically challenging. Our work only became possible through a close collaboration with the CDC and use of its biosafety level 4 facilities.”

Results from the study (Human Ebola virus infection results in substantial immune activation) show that, in contrast to what previously believed, the four patients responded to the Ebola virus with immunoactivation. Combined results from several prior studies indicated, instead, that the virus may induce immunosuppression. Lead author Anita McElroy said in the press release: “Our findings counter the idea that Ebola virus infection is immunosuppressive, at least in the patients that we were able to study. They also demonstrate the value that supportive care may have in enabling the immune system to fight back against Ebola virus infection.”

High levels of both B and T cell activation were present in all four patients. Plasmablasts, proliferating precursor cells of short- and long-lived plasma cells (which produce large amount of antibodies), represented 10–50% of the B cell population, compared with less than 1% in healthy individuals. Activated CD4+ T cells ranged from 5 to 30%, compared with 1–2% in healthy controls, while over 50% of the CD8+ T cells expressed markers of activation and proliferation. Immune activation was present even after the virus was cleared from the blood and patients had left the hospital.

The patients’ CD8+ T cells — which directly kill infected cells — targeted several Ebola virus proteins. A major target was an internal protein called NP. The researchers suggest that NP could be added to existing vaccines to generate stronger T cell responses, as vaccines now entering clinical trials in Africa contain only the external glycoprotein called GP.

McElroy said: “CD8+ T cell responses have been associated with vaccine protection against Ebola infection in some animal models, but the relative importance of T cell responses, compared to antibody responses, in driving survival and vaccine efficacy in humans is not known. We anticipate it will be an active area of research in the future.”

One of the reasons why ebola is so pathogenic and fatal may be due to the fact that this virus is very new in terms of exposure to humans. The earliest known outbreak was in 1976, which is not long ago at all. It takes many generations for evolution to take place for human population as a whole to increase immunity against a pathogen. Also, the disease’s symptoms in many parts of the body and it presence in bodily fluids indicate that the virus can infect many parts of the body including immune cells. An unfamiliar virus with promiscuous specificity is a double threat that may have not only killed people with its pathogenicity, but also by the body’s overwhelming immune response.

This is a very wise observation and quite possibly very true! However, counter example to the train of thought that time gives immunity is in the case of the notorious Mycobacterium Tuberculosis, or TB. TB has evolved with mankind for centuries, even estimated to have been with mankind since before our ancestors left from Africa. This means that our body’s immune system has been dealing with the same pathogen over the course of thousands of centuries, and yet is no closer to being able to naturally deal with the pathogen outside of vaccination. However, this situation is albeit a very unusual and difficult one, being that every time our immune system evolved so did TB itself, even coming to a point where several strains could inhabit one person at once! Still, you make an excellent point that it is by Ebola’s vast and promiscuous specificity that deals such a heavy blow in the fight against the immune response. One can only hope that given enough time our immune system could develop an immunity to a given pathogen, but let it not be forgotten that as our immune system grows and expands, so does its enemies, becoming craftier and more deadly all in their own time!

Another factor to consider is that less lethal diseases are usually more easily transmitted, because they kill people more slowly. This puts evolutionary pressure on diseases to reduce their lethality. Future strains of ebola may be less dangerous than the current strains.

Note that, while TB is very dangerous, it is also very slow (usually). This gives it a lot of time to spread through a population.

Now that we know a little more about ebola and effective ways to cure it I think it is very important that we utilize the techniques used to cure the 4 patients in the US in other countries. In order to decrease the spread of the disease we must stop it at its source. I know it cost alot of money to make the vaccines here in the US and also even more money to get them out to other countries but we have to invest money to save lives. People travel in and out of the country daily which means that if we dont combat this disease there is a possibility that we will have more outbreaks in the future as we did a few months ago.

I don’t think the issue lies within the lack of funding of the Ebola Virus in other countries. I think It has more to do with the lack of education and cultural differences in the countries where this virus is most prevalent. For example, one of the main problems in stopping the spread of this virus in Liberia has been their traditional burial process which usually involves the washing of the corpse by family members. There have also been reports that people are afraid to go to the isolation wards because of the measly conditions that they are kept in.

Ebola is a relatively new infectious disease that has recently garnered the attention of both scientists and human populations across the world due its potent nature of pathogenicity. Previously overlooked because of the rarity of transmission and few number of recently reported cases of outbreak, Ebola has as of late become the focus of hysteria amongst civilians who fear the possibility of somehow unknowingly contracting the fatal disease. Since its ascension into the limelight of news media salience in March 2014, the Ebola virus has remained enigmatic in regards to its pathogenicity and the immune responses raised to combat infection. Consequently, the roadblocks that have hindered an effective means of vaccine development have resulted in the Ebola virus transforming into somewhat of a medical Lochness Monster; its true nature seemingly always obscured and looming behind the near shadows of what has yet to be discovered by researchers and scientists.

However, the findings presented in the study above have effectively changed the way the Ebola virus and resultant human immune responses to contraction are being conceptualized. In other words, evidence in support of immune activation to human Ebola Virus infection in the form of activated effector CD8+, CD4+ and plasma B cells, provides a viable basis for vaccine development and other methods of preventive care that would lead to the accumulation of specific memory T and B cells poised for subsequent infection. As a consequence, the potential for identification of the elusive targets of successful immune activation are greater than ever and have an integral role in fate of vaccine development. For example, in the article, “A long-lasting, single-dose nasal vaccine for Ebola: a practical armament for an outbreak with significant global impact”, Jonsson-Schmunk and Croyle discuss the recent approval for fast track status of a form nasal immunization which causes an immune response directly at the mucosal surface, the initial site of Ebola infection, thereby allowing clinical testing as soon as possible. Therefore, it is with great hope that the unveiling of the specific functions and roles of T cell and antibody responses in regards to the Ebola virus will continue to further the understanding of the mechanisms behind this debilitating disease, and lead to the development of an efficient and reliable vaccine for the populations which require it most.

Ebola is a virus that, until this recent work with the survivors in the above mentioned press release, had been thought to function much like AIDS. That is, its main offensive objective is to decrease key immune cells functioning (more specifically, killing off CD4+ T cells). It was thought that Ebola was much more vicious than AIDS in its immunosuppression, even preventing interferons from signaling antibodies to attack. Once the immune system is down, the virus would replicate and begin to destroy tissue, especially collagen, causing blood clots leading to external hemorrhaging. The findings that Ebola is not immunosuppressive is a bit surprising. It would make sense in some ways because some of these immune cells are involved in coagulation and clotting which lead to the burst vessels and eventual organ failure. This could also explain the large amounts of accounts of a patient’s immune system attacking its own cells, creating large autoimmune issues.

It goes without question that the media provided a popular growing trend that illuminated many people to the lingering threat of the Ebola virus, ever since the outbreak in West Africa. The proportions on the statistics is mind blowing considering thousands of deaths, with rising cases until the epidemic is controlled. The news became even more rampant when, coincidentally enough, the four patients affected with Ebola were right down the street at Emory Hospital. Therefore, I found the study’s focus for immune activation to be beneficial, despite its limitation.

Undoubtedly, the limitation for the study considers the amount of individuals assessed, as well as the limits placed on investigating the human immune response from the elevated levels in biosafety containment. Nonetheless, it is fascinating and important to note the recent findings for Ebola eliciting an immune response despite contrary ideas suggesting immunosuppression. The aforementioned article by Anita McElroy in the blog was of interest since it depicts the presence of CD4+, CD8+ and IgG-positive plasmablasts in flow cytometry plots. Because of the elevated levels of T- and B- cell activation, it is a wonder how Ebola is able to thwart actions by the immune system.

Once this negative-stranded RNA virus has strategically replicated itself within the body’s mechanism, it seems to taunt the host despite antigen recognition triggering a humoral and cell mediated immunity when compared to control groups. However, the recognized Ebola virus nucleoprotein serves as a spark toward vaccine development. Even more is to consider the article cited by T. White previously, since action is being taken through projects like the single-dose nasal vaccine study by Jonsson-Schmunk and Croyle, which might prove to be miraculous as more research takes hold. To expound as another intriguing option considers a study by Tan Dun-Xian and colleagues who see melatonin as a potential treatment option for Ebola. There seems to be no limits in terms of how to defeat Ebola, therefore I am optimistic for finding a solution that can reach greatly-affected areas like West Africa.

Ebola, in general, although often hyped in the media is not a big killer around the world. When just considering Africa, AIDS and malaria kill far more people than Ebola. But besides these points what is important is that if improvements to vaccines are made they need to fit a few criteria. The first is that they have to be inexpensive to produce and distribute. International communities are helping to fight the outbreak, but the problem is local governments in West Africa are not equipped to handle the epidemic. In contrast, the United States, which has the highest GDP per capita of any other country, was able to save these four patients. This success is due to the highly skilled healthcare professionals and the amount of money the USA invests in healthcare, however, this is not feasible in the places most affected by Ebola. Thus, the total cost has to be an amount which organizations like the UN is willing to supply. Secondly they must be proven to work with humans, or in the case of NP, generate a larger T cell response. Proving this would require clinical testing with patients infected with Ebola, which raises ethical concerns when it comes to the placebo (non-NP vaccinations) possibly not receiving a life-saving treatment. If, in fact, the T-response was greater this will prove to be crucial in the adaptive immunity’s ability to fight off the pathogen. A higher T cell response will cause more B cells to differential as well as more cytotoxic T-cells able to attack virus-infected cells. Overall I am intrigued, and I wish these researchers the best in developing treatment for this horrible ailment.

Since the outbreak of Ebola in West Africa in 2014, medical professionals and researchers have been desperately been searching for ways to combat this horrifying disease. The lack of information and efficient facilities to study the disease have made it difficult to find a safe and efficient vaccine. The body’s response to the virus, according to the study by Anita McElroy in the blog, is immunoactivation, with the NP protein as the main target of the T-cells. Several scientists have been studying the glycoproteins of Ebola virus, specifically Zaire Ebola virus for the past 10 years and these are the only vaccines going to clinical trial in Africa. A study by Wahl-Jensen, Kurz, Hazelton, and several others in the Journal of Virology called the Role of Ebola Virus secreted glycoproteins and virus-like particles in Activation of Human Macrophages found that glycoprotein (GP) by itself does not activate macrophages. It must be expressed on the surface of a virus-like particle, manifesting a strong activation of macrophages. Another study by Warfield and Aman called Advances in Virus-like particle Vaccines for Filoviruses, tested virus-like particle vaccines for filovirus hemorrhagic fevers on rodents and non-human primates with success. The vaccine “incorporates GP, the matrix protein VP40 into virus-like particles after coexpression in eukaryotic cells” and can be manipulated to include NP as well as other proteins in order to elicit a potent innate immune response. Virus-like particle vaccines look like a promising vaccine for use in the near future once clinical trials have been completed and could be able to help in the prevention of future outbreaks.

Interestingly enough, researchers in and associated with World Health Organization (WHO) are working feverishly to find a possible vaccine and even some form of a management system for the Ebola virus disease (EVD). I agree that West Africa’s rampant outbreak of Ebola is as a result of deficits in the health care system. Even though, health care workers came to Africa’s aid, successes in combatting the outbreak proved futile. As I am in agreement with Henry that workers lacked equipment, sterile infrastructure, and trained professionals. Even the lack of knowledge amongst the peoples about transmission of the virus led to the rapid spread.

EVD has devastated human health in Africa, as health systems were and still is inefficient to cope with the gravity of such an outbreak. Thomas Kreil, author of “Treatment of Ebola Virus Infection with Antibodies from Reconvalescent Donors”, offers insight into “scarcely supported” but “positive” clinical methods for treatment. There may be positive health incentives by using “whole blood” or “plasma transfusion from reconvalescent donors (persons who have recovered from Ebola infections.” Apparently the antibodies produced during the infected person’s immune response may offer treatment alternatives.

However, alternatives, as mentioned earlier, may pose some issues. One, because in the case of the woman with sickle cell who survived the Ebola infection, how immunogenically friendly would it be to use her whole blood or plasma for transfusion purposes? Blood donations from individuals with sexually transmitted infections who have recovered from would require blood screening. The WHO requires that “pre and post donation testing” of donated blood within a 48-hour timeframe. What if the majority of recovered individuals had other predisposing factors for escalation of the virus?

There is never always a direct method of finding treatment that suffices for mass populations. Kreil states the uses of whole blood poses issues of the blood being treated by virus-inactivated methods and the amount of blood donated within a particular time frame would be insufficient. Moreover, the study purports, “Transfusion of plasma alone would alleviate a number of the concerns inherent in the use of whole blood,” thus reducing the limitations of use of whole blood. Other sought out means of finding mean to treat infected persons may prove effective and valuable to the human resources in West Africa.

According to Teri Shors, author of “Viruses,” states that, “Ebola was named after the Ebola River located in the northern Democratic Republic of the Congo (formerly Zaire), where the virus first appeared in 1976.” This information infers that Ebola is a reemergent virus that has been documented approximately 38 years ago. It is understandable why it would be deemed as “mysterious,” because it has certainly been awhile since it had rear its ugly head amongst populations.

With regards to this re-emerging virus, vaccination research should take a “hedgers” financial approach by trying to remedy the situation as it presents itself to prevent the worst possible outcomes in the future. In other words, trying to develop vaccines for Ebola at its earliest recognition can potentially help remedy future catastrophic outcomes for worldwide population mortality.

ProMED-ahead digest issued a “Sputnik” news article which illustrates data on the vastness of infection in countries around the world. The data is dated back to October 25, 2014 listing countries affected by the viruses’ outbreak, countries such as Guinea and Sierra Leon which show the highest confirmed cases in the world as reported for 2014. Places like Spain, U.S., Mali, and Turkey had fewer confirmed cases ranging from 1-3 patients; where the U.S. has had 3 confirmed cases.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) some symptoms of Ebola are “Fever, Severe headache, Muscle pain, joint and muscle aches, Weakness, Fatigue, Diarrhea, Vomiting, Abdominal (stomach) pain, Unexplained hemorrhage (bleeding or bruising) etc.”

In discovering an effective vaccine for Ebola, requires a practical understanding of host/pathogen interaction and its evasion of humoral and T-cell-mediated immune responses. There were documented reports that a Sickle Celled diagnosed woman from Sierra Leon survived the Ebola infection; moreover, her daughter that was in contact with her died as a result of infection. This raises a question about how is a healthy individuals’ immuno-competence weighed against someone that show signs of an immunocompromised immune system.

When an individual becomes infected with Ebola, high concentrations of the virus accumulate in the secondary lymphoid organs damaging them. The individuals’ mortality is as a result of “viremia” (virally blood borne). This is an account of immunosuppression. However, as recent research verifies there is an “immunoactivation” in the infected individual. Could it be that clinical care offered during onset of the viral infection accounted for this “immunoactivation?”

Consider the confirmed case of the Ebola infection in the Sickle celled woman who survived. She was taken into emergent care of a treatment center after she complained of joint pains, weakness, and an inability to walk, symptoms associated with Sickle Cell and Ebola. On the other hand, the woman’s 10-month-old daughter who remained home with the father passed after 5 days with symptoms of high fever. Can research conclude the tipping point between survival and mortality individuals whether they are immunocompetent or immunocompromised? Is there a correlation between time of care and survival rates?

It is a tradeoff. There is no perfect system, there will be loopholes found. A healthy system is more attractive than an unhealthy system because, in a healthy system, pathogens consider the availability of resources they can exploit. Healthy individuals without sickle cells do not experience the pains and other health issues that people with sickle cell go through. On the other hand, people with sickle cell are not as healthy, but their internal environment is not conducive for the pathogen. Just like in malaria, people with sickle cell do not have malaria because their red blood cells are not favorable for the development of the merozoites since there is not enough oxygen. Another example of this situation is observed in children with Niemann Pick Type C. NPC is as a result of malfunctioning of some cholesterol genes which are functional in healthy individuals. These genes are essential for deadly infections like HIV and Ebola to infect a person. Since children with NPC have unfunctional NPC cholesterol genes, they are protected from getting infected by HIV for instance, but they will not live long because the genes are critical for other activities for proper body function. It will be interesting to see the result of researching the connections between sickle cell and Ebola.

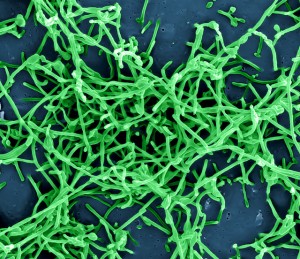

Ebola is a negative sense ssRNA virus of the family filoviridae. Filoviruses are generally known for their ability to suppress the immune system response by attacking the main antigen-presenting professional cells such as Macrophages and Dendritic cells.(Fritz 2012) The study mentioned above seems to contradict this immonunosuppresive characteristic of the Ebola Virus but I think that it may be too early to make such a conclusion. For one the sample size is way too small for the findings to be scientifically conclusive. The study seems to point out another important point that may be useful in the fight against this virus: if patients receive enough supportive care to enable them to survive the hemorrhagic fever then their immune system can overcome the viral infection. This study should be conducted a larger scale, perhaps in the regions where the viral infection are more common such as Guinea and Liberia.

The sample size of four is definitely statistically insignificant, but technically there have been other stories where supportive care given have resulted in the survival of Ebola infected patients. For example, a 22 year old nursing student in West Africa suited up in trash bags and with the consultation of a doctor through the phone she ended up saving three out of four of her own family members as well as prevented herself from becoming infected. Stories such as these support McElroy’s statement regarding “the value that supportive care may have in enabling the immune system to fight back against Ebola virus infection.”

1. http://www.cnn.com/2014/09/25/health/ebola-fatu-family/

Ebola virus has been the largest and most long-drawn-out epidemic in history presented by media all over. The tragic outbreak in West Africa was the wake-up call to get ready for future epidemics. There was some research that the virus can transform into an airborne disease. There were many factors which could have resulted in failure to control this epidemic; such as, many people facing poverty, not having good health-care system, affected individuals responding late to this disease and spiritual reasons. There are experimental treatments still in progress; however no specific effective medication known. There are several experimental preventative vaccines been established but none is approved to clinically use in humans. According to the Journal of Virology’s article, Ebola Virus Pathogenesis: Implications for Vaccines and Therapies, the first successful Ebola vaccine (combined with plasmid DNA and genetic immunization) was developed from the porcine. It was challenged moment for those who have been survived by the professional health-care workers who worked really closely to overcome this virus infection. It is very hard to study in humans, there will be inadequacy to this study in exact mechanism of immune response to this disease. The infection progress (increase in T cells and B cells response) is very rapid and fever is spotted right away due to the release of cytokines by macrophages. Many research also suggests that antibodies would not clear the infection itself, cellular immunity also plays important role in the clearance of the virus.

The Ebola virus is a virus that is spread from infected animals to humans by bodily fluids and air. The filoviruses cause hemorrhagic fevers, which gives the virus an opportunity to infect the host. There has been several patients with arthritis that showed “ higher anti-Ebola IgG ELISA titers,” which indicated that the virus had an increase in producing antigens. The ELISA test for IgG and IgM were measured to indicate whether the viral infection was spread among people like family, residents, medical staff, and other patients. The ELISA test has also shown a false-positive result, which then requires for further tests to be done.

Ebola antibodies were then measured in those who have an acute infection, in which evidence of the activation of cytokines was seen in mRNA. There are soluble glycoproteins that are circulating and are able to make more once the virus has attacked the glycoprotein. This will alter the immune response as the virus now dominates the genes. There have been many proposed mechanisms that leads to “ the parenchymal cells, macrophages, and endothelial cells ” to undergo necrosis. The therapies that an individual with Ebola along with the necrosis of many organs will impact the rate in which one will be able to survive as the immune system has been ineffective. There isn’t a vaccine for Ebola, but there are proposed mechanisms that are being done to help protect against the virus. There has been a high tittered anti-Ebola serum for baboons with the Ebola virus, which has been effective in guinea pigs, but not in monkeys and mice. Through the production of monoclonal antibodies that were taken from bone marrow of survivors of the Ebola virus, a potential therapy can be developed.